High Performance Aviation

About Oxygen in Aviation

By Hank Gibson, Gold Seal, CFI, CFII, MEI

Last Monday, I went with a group of pilots to NASA to take a high altitude training course dealing with altitude in aviation. Though I was unable to participate in the altitude chamber flight at the end of the day, it was still a valuable refresher for me on the effects of high altitude. Hopefully, after you read this article, you will be more educated on the affects and dangers that high altitudes have on pilots, making you safer. (All information that follows was taken from NASA’s High Altitude Training Seminar, unless otherwise noted).

What is Hypoxia?

Hypoxia, defined straight from NASA, is “a state of oxygen deficiency in the blood, tissues, and cells sufficient to cause an impairment of mental and physical functions.” Basically, it ain’t good. How does this oxygen deficiency occur in aviation, you ask? Good question.

The higher a pilot goes in the earth’s atmosphere, the atmospheric pressure and the partial pressure of oxygen in the air both decrease. At sea level (I’m going to use the units that NASA gave us), the atmospheric pressure is 760mm Hg (equivalent to 29.92in Hg) and the partial pressure of oxygen is 100mm Hg. The oxygen saturation of the body is at 98%.

As altitude increases, both atmospheric pressure and the partial pressure of oxygen decrease, measuring 522.6mm Hg and 60mm Hg at 10,000 feet, respectively. Up at that altitude, the oxygen saturation of the body is down to 87%. At sea level, medically, when a person’s body gets down to 87%, doctor’s give that person an oxygen canister to carry around. You see lots of older folks with them. In aviation in an unpressurized cabin, this is the level a pilot’s body is at. Mental and visual capability is impaired as well as other bodily functions. That’s only 10,000 feet!

Different Types of Hypoxia

NASA told us about four different types of hypoxia in aviation, each affecting a different system of the body. The first is hypoxic hypoxia, a lack of oxygen to the lungs. This would be the most common form of hypoxia for pilots due to breathing air at a reduced atmospheric pressure. The cause could be anything from improper equipment usage to a rapid decompression.

Hypemic hypoxia is any condition that messes with the blood’s ability to carry oxygen. Where this pops up in aviation is with carbon monoxide poisoning. CO poisoning can either come from a leak in the exhaust system creeping into the heater or smoking. Our NASA instructor said if you smoke, that automatically put’s your body at 8,000 feet, even at sea level. If you don’t smoke, don’t pick it up. If you do smoke, please, for your sake, look into a program to stop smoking.

Histotoxic hypoxia prevents the cells from using the oxygen that is already there as they normally would. The cause? Alcohol and drugs. Alcohol and certain drugs inhibit the cells from utilizing oxygen rich blood. Don’t drink and fly (FAA regs) and be extremely careful with over the counter medication. If it makes you drowsy, don’t fly after taking it. Most prescription drugs don’t mix well with pilots either.

Finally, stagnant hypoxia affects blood circulation. You have probably experienced this when your arm or your foot have “fallen asleep.” Other causes of stagnant hypoxia that can be more dangerous in aviation are hyperventilation, g-forces experienced in aerobatic training, or even extreme hot or cold temperatures.

How to Identify Hypoxia

The folks at NASA were very specific when they were teaching us pilots how to identify hypoxia in someone. There are signs (everybody would experience these) and symptoms (each individual would get different symptoms). Our instructor also told us that a person’s symptoms changed with age, so mine would be different in twenty years.

Here is a list of hypoxic signs that would show up in everyone:

- Increase rate of depth and breathing

- Cyanosis (blueing of the lips and fingernails)

- Slurring of speech

- Poor coordination and mental confusion

- Euphoria

- Belligerence

- Becoming lethargic

- Unconsciousness

Not everyone will experience all of these signs. Euphoria usually doesn’t change to belligerence, but these are what to look for in yourself and others. NASA also gave us a long list of possible symptoms, ranging from numbness and fatigue to nausea, but the instructor was very specific in stating that symptoms are different for different pilots. Basically, a symptom is anything that would be abnormal for you, personally.

Hypoxia Remedies

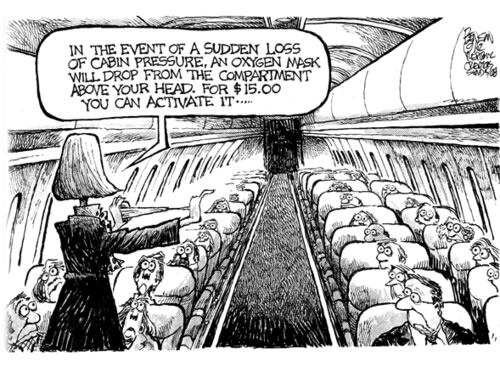

So what do you do if you discover you are becoming hypoxic? The FAA and NASA both emphasize the time of useful consciousness. Basically, that is the amount of time at certain altitudes that a pilot will remain conscious in a hypoxic state before he passes out. It ranges anywhere from 20-30 minutes at FL 180, to 9-12 seconds at FL 430 for a slow decompression. For rapid decompressions, the time is much shorter. So, act quickly.

The first step is to get on 100% oxygen. Check your supplemental oxygen gear to make sure it’s sealed properly. Then, control your rate and depth of breathing and get down below 10,000 feet as quickly as possible. If ATC asks, tell them it’s an emergency. Do not take this lightly because it can turn in to a dangerous situation very quickly.

What if you don’t have any supplemental oxygen? Well, what were you doing above 10,000 feet? Get your butt down to a lower altitude ASAP and think a little bit more when picking your altitude next time.

Altitude in aviation can be dangerous if you aren’t prepared. For those unpressurized, un-oxygenated pilots, keep it below 10,000 feet. Your brain will work better. You don’t want to sound like this guy.

Would you like more information?

Send us a message below.